12.11.2025

Announcing r1

A Foundational Model for Small Molecule Drug Discovery

By The Rhizome Team

Today we are excited to announce the release of Rhizome's Foundational Model for small molecule discovery, r1. This is the first in the r-series of foundational models that we will launch. Please read more below and you may contact us at x@rhizome-research.com, fill out our form here or find us on LinkedIn for partnership opportunities.

Fragment-based Small Molecule Generation

Modern drug discovery usually requires optimizing validated hits rather than generating from scratch, a nuanced challenge in fragment-based generation where conventional approaches often fail to offer adequate control to preserve established structure-activity relationships. Rhizome's r1 overcomes this lack of customizability by delivering efficient chemical space sampling and the precise control required for native scaffold hopping, R-group exploration, and linker design.

As a diffusion graph neural network with 245M parameters, the model learns directly from molecular graphs. Trained on approximately 800 million molecules, it possesses an intrinsic understanding of chemical rules by learning the conditional distribution of atoms and bonds given molecular context.

While r1 is capable of de novo molecule generation, our focus lies in fragment-based drug discovery, an approach analogous to image inpainting or code completion. It generates novel molecular structures while respecting user-specified constraints on scaffolds, generation locations, heavy atom counts, ring systems, and other structural parameters. This constraint-aware design makes it particularly well-suited for practical drug discovery tasks. The model functions as an intelligent molecular editor, think Figma for drug design. Our architecture design ensures that the model generates genuinely diverse molecules, not just variations with trivial modifications such as added carbon chains, but meaningfully different modifications of the scaffold that expand the chemical sub-space.

To demonstrate the capabilities of Rhizome's r1, we present a simple example: scaffold decoration performed on the indole scaffold. This task is inspired by a few common drugs, including Ondansetron and Indometacin. Two attachments on the five-membered ring were selected. There are two major types of decoration that can happen: i) chain fragments as seen in indometacin and ii) expansion of the multi-ring system as seen in ondansetron.

This task requires the generative model to produce fragments at user-specified locations. To our knowledge, only two publicly available models offer this capability, SAFE-GPT and GenMol, both of which use Sequential Attachment-based Fragment Embedding (SAFE) representation for small molecules. SAFE-GPT treats molecular generation as a sequence completion problem through manipulation of the input, while GenMol as a masked diffusion sequence model distinguishes itself with a fragment remasking strategy that selectively masks and regenerates specific molecular parts. In the following comparison, we evaluate the quality of molecules generated by Rhizome's r1 against these two benchmarks.

SAFE-GPT exhibits a strong bias toward generating short chains. As chain length increases, the model produces an excessive number of heteroatoms, resulting in unrealistic structures. GenMol generates more diverse fragments, but the sizes vary significantly. Larger fragments generated by GenMol also tend to contain an overabundance of heteroatoms. Both models share common limitations: users cannot control fragment size or specify multi-ring system expansion. These limitations do not apply to r1. Users have full control over both the type and size of fragments generated. Our results demonstrate that r1 successfully produces diverse molecules through both chain fragment generation and multi-ring system expansion.

However, this task remains relatively simple compared to real-world drug discovery scenarios. In the following section, we present a challenge where no other generative model can be readily applied to assist in the discovery of new drug-like candidates.

AI-assisted Drug Discovery: EZH2 as an Example

EZH2 is a histone methyltransferase and the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), responsible for silencing gene expression through the trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27). Its study is critical because aberrant overexpression or mutation of EZH2 drives the progression of various cancers, including prostate and breast tumors, by suppressing essential tumor suppressor genes. Consequently, EZH2 has become a validated therapeutic target, leading to the development of selective inhibitors like tazemetostat which are now FDA-approved for treating specific malignancies such as follicular lymphoma and epithelioid sarcoma.

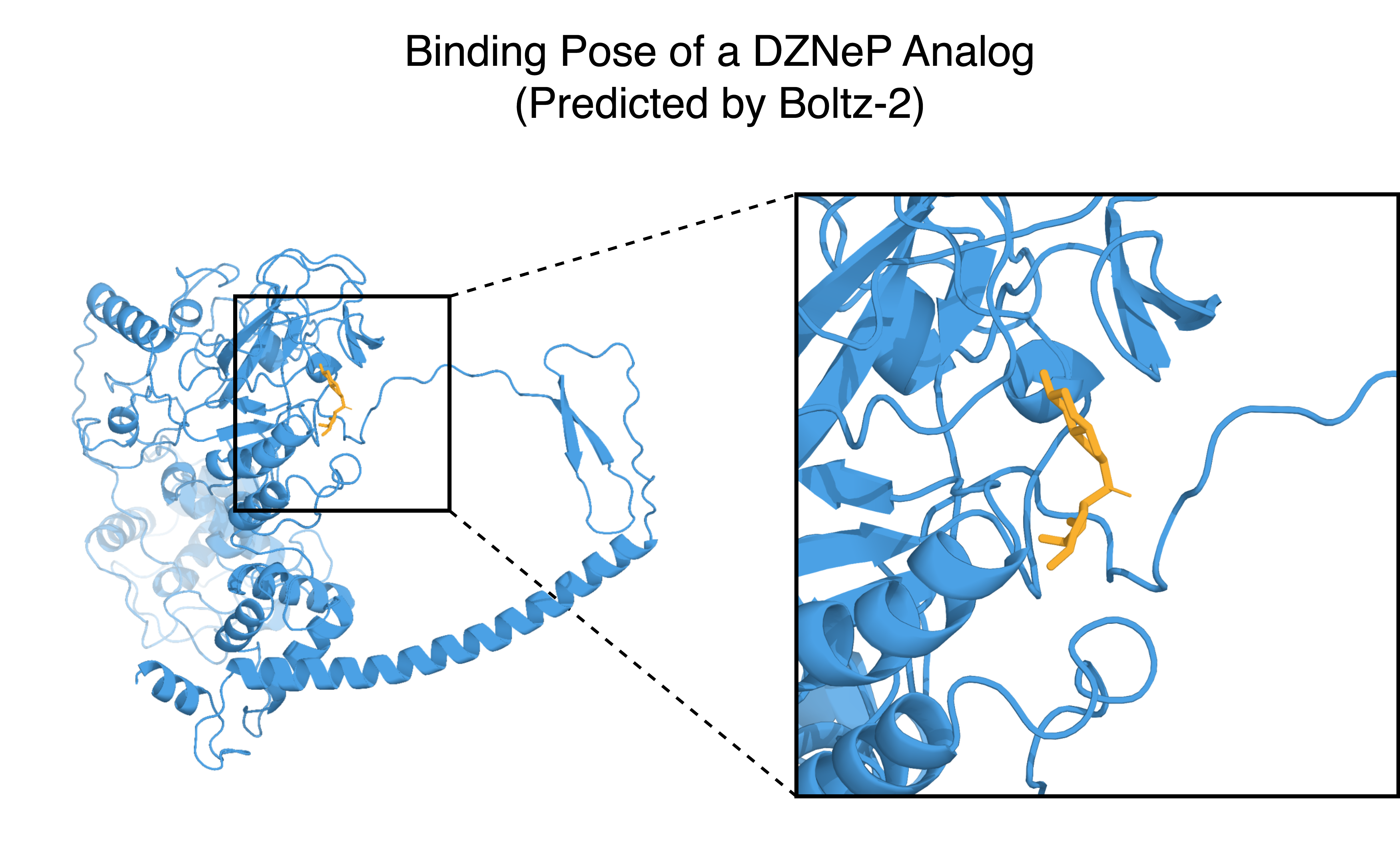

The discovery of potential EZH2 inhibitors often centers on modifying existing patented compounds. To circumvent prior art, we applied a core replacement strategy using two known inhibitors as reference molecules: EPZ-005687 (indazole core) and DZNeP (azabenzimidazole core). By generating novel systems to replace the core of each inhibitor, we aim to discover new scaffolds with comparable binding affinities that may be patentable. For each reference molecule, 100 diverse analogs generated via core replacement were evaluated using the Boltz-2 model. The predicted binding affinities are shown below.

Our r1 model successfully identified analogs with stronger predicted binding affinities for both reference molecules. The two groups exhibit different distributions: the mean binding affinity of EPZ-005687 analogs is higher than that of the reference molecule, while the mean for DZNeP analogs is lower. This suggests greater potential for discovering scaffolds that outperform DZNeP through core replacement. For EPZ-005687, further optimization may require specific modifications to peripheral groups to fine-tune binding interactions.

We also show how the generated DZNeP analogs with lower binding affinities cluster into different groups below. Fused bicyclic systems show the greatest improvement in terms of binding affinity, which suggests that a semi-flexible system is preferred by this target protein.

This example shows the potential of a combined pipeline of a deep generative model and a physics-based AI evaluator. Within one iteration of random generation, the binding affinity of EZP-005687 was improved by -0.9 kcal/mol, while the binding affinity of DZNeP was improved by -1.6 kcal/mol. To further support our strategy of exploring candidates that are similar to the reference molecule, in the following plot we also show how the range of binding affinity changes with respect to the distance between the analog and the reference molecule evaluated using r1 embeddings. When the analogs are sufficiently different from the reference molecule, naturally a wide range of binding affinities can be explored, but the population mean can also fluctuate, necessitating the need for an efficient optimization algorithm for extended discovery.

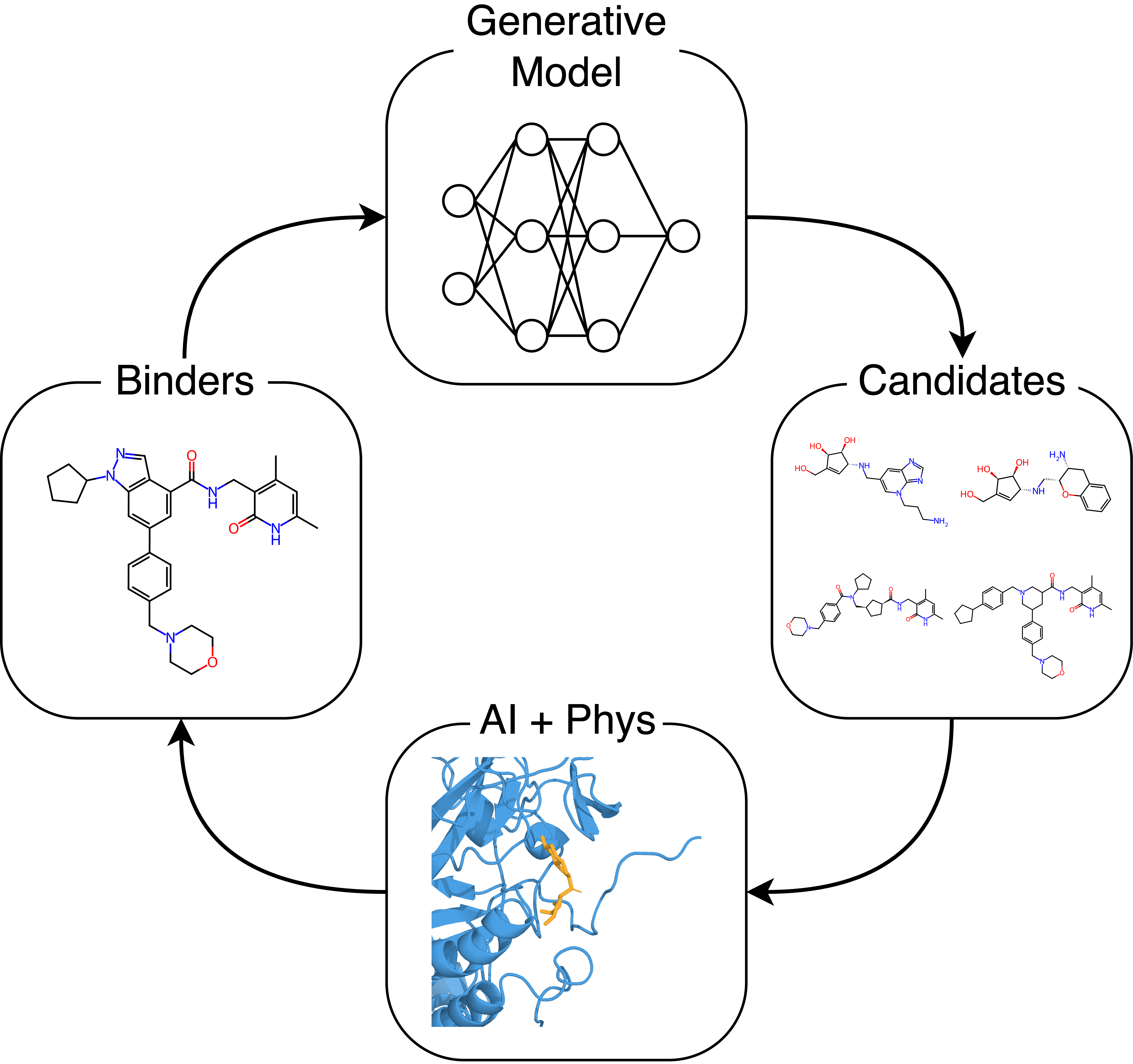

Our Vision: Agentic Discovery

Drug discovery is fundamentally a search problem. While the chemical space is vast, the number of potential binders for any given target is limited. The key is constraining the search to a relevant sub-space and mapping it efficiently. With enough constraints, the valid molecules become manageable, but only if the generative model avoids strong biases and produces diverse candidates.

Our goal is not to build models for their own sake, but to deploy them in real drug programs with real consequences. For experienced drug developers, this means everything from hit finding to lead optimization can begin faster and proceed more efficiently and accurately, especially when starting from known binders or inhibitors. Given a reference molecule, our generative model explores the adjacent chemical space by producing thousands of candidates, which our physics-based pipeline rapidly screens for improved efficacy. With the addition of multi-objective optimization incorporating patentability, solubility, synthetic accessibility amongst other properties, the r1 pipeline becomes an automated discovery loop. One then can gather how a multi-agent system can autonomously orchestrate, execute and analyze r1 and MolSim to get to agentic discovery. If one cannot, we will make it more clear when we open source a multi-agent system for running Docking and MD.

Beyond traditional workflows, our models enable strategic IP applications. Given prior art, r1 can be applied to perform scaffold hopping, gradually departing from reference molecules while preserving the binding pose. This capability supports both offensive patent circumvention and defensive IP protection, depending on the objective of specific drug discovery campaigns. Powerful AI technology changes the dynamics of IP strategy and we will share more learnings as they come.

While this is only a demo and a taste of what we are working on, we have some exciting work in the pipeline we'll be sharing with the community - specifically the integration of MolSim, our RL pipeline and the launch of r2, which will be an order of magnitude more capable than r1.

You can contact us at x@rhizome-research.com, fill out our form here or find us on LinkedIn for partnership opportunities.